If you have ever dropped your bike in a parking lot, you are going to like this article. If tight U-turns make you cringe, keep reading. There are a few tricks ahead to make slow and tight, easy and fun.

We Are Creatures of Habit. Which glove do you put on first? It’s usually the same one every time. We do things the same way over-and-over for many reasons— it works— I like it that way— It’s what I was taught to do. If we do something often enough it becomes a habit. A conditioned reflex. But what happens when a habit doesn’t work? That’s when I step-in— I’m a rider coach. My job is to help riders solve problems. Sometimes that means having to un-learn bad habits. For a fix to be long-term I usually begin with some mental and emotional coaching before we get to the physical—mind and heart first, then the skills.

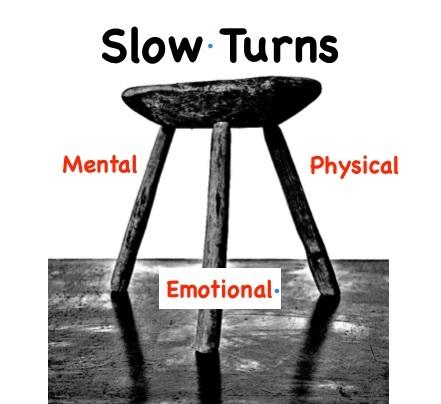

So what does all this have to do with slow-speed turns? The secret to being able to consistently do tight U-turns is to learn a little about the physics involved (mental) before moving the handlebars (physical). Then, with practice, any nervousness is replaced by poise and confidence (emotional).

The Mental Part of Slow Speed Turns

Let’s get personal. What goes on in your head when you realize you have to make a tight U-turn? Okay, okay, maybe we don’t want to know. But, I’ll bet there is a small voice that says, “lean-in with the bike during the turn.” That voice, thought, belief or habit— whatever you want to call it— is common because the majority of motorcycle turns are fast. If we don’t lean in, it feels like we are being pulled to the outside and the bike is leaving us behind. We hang-on and lean-into avoid that feeling of separation. We are conditioned mentally, emotionally and physically to lean our body in with the motorcycle towards the center of the turn. Unfortunately, if we at do that at slower speeds, we will probably crash. Gravity will pull us down. The take-home message is we must have two ways to turn the motorcycle. A high-speed method and a slow speed method. Let’s start with a brief review of high-speed turns.

SIDEBAR: Put a few physicists in a room and ask them, how fast is fast? Where is the break between a slow-speed counter-balance turn and a high-speed counter-steering turn? They will argue endlessly about the variables of mass and radius and blah, blah, blah. You will probably not get a direct answer. So the best opinion I can offer based on almost 50 years of experience, study, and research, is that the split between slow and fast-speed turn techniques occurs at about 7-10 mph (11-16 kph). About as fast as you can walk or a slow jog. Slow speed turns are usually in first gear.

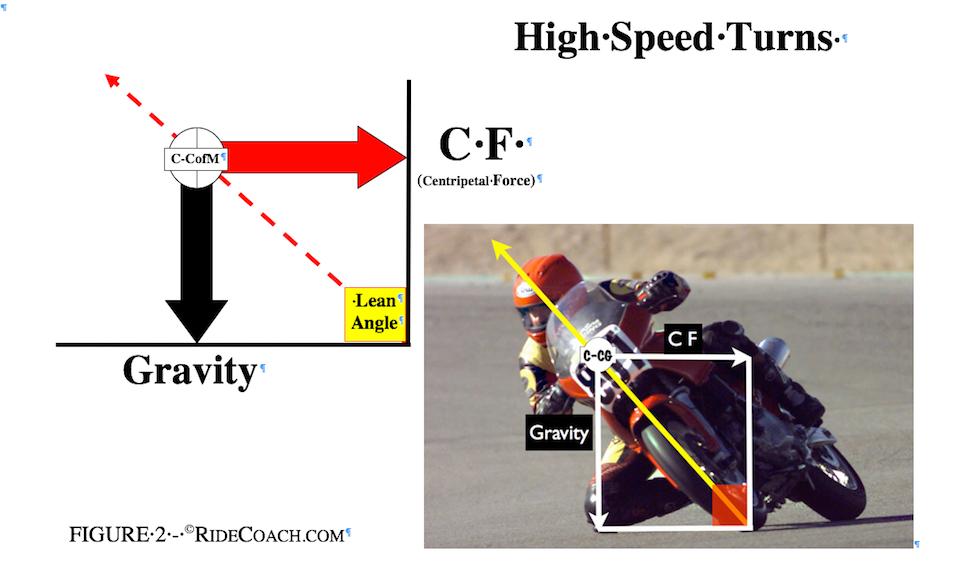

High Speed Turns

We initiate a fast turn by turning the handlebars opposite the direction of intended travel. You know, push right to go right. Counter-steering becomes a habit so strong we rarely think about it anymore. We just do it. The purpose of counter-steering is to create lean-angle. So we only hold the counter-steer push long enough to get down to whatever lean angle we need for that turn and then we stop the push. We DO NOT counter-steer all the way around the corner. The perfect lean angle for a given high-speed turn is when two forces are in balance: gravity pulling us down and centripetal force lifting us up. Simply stated, if we have too much lean gravity wins and we take a low-side fall; too little lean and centripetal force wins causing a high-side crash or running wide. We lust for the perfect lean-angle because when we find it, it feels like we are on rails around the curve. The bike feels solid, smooth and steady.

Remember, because most turns we take are fast, our bodies are trained to lean in with the bike. Counter-steering and leaning-in are strong, powerful habits that do not work for slow speed turns.

Remember, because most turns we take are fast, our bodies are trained to lean in with the bike. Counter-steering and leaning-in are strong, powerful habits that do not work for slow speed turns.

Slow Speed Turns Are Different. In a slow speed turn, the only force we have to manage is gravity pulling us down. There is no force trying to lift us up to the outside of turns. Well, to be precise, there is a force but it’s so small we don’t have to worry about it. For you physics majors, I am referring to the force vectors of inertia and centripetal acceleration but let’s not go there now.

We use direct steering for slow speed turns; counter-steering is NOT necessary. Just point the front tire where you want to go. It is sometimes called, “point and shoot” steering.

Slow-speed turns are called “counter-balance” turns because we use our body weight and position to offset the pull of gravity. This is also called “counter-weighting.” Understanding why counter-balancing works requires some discussion.

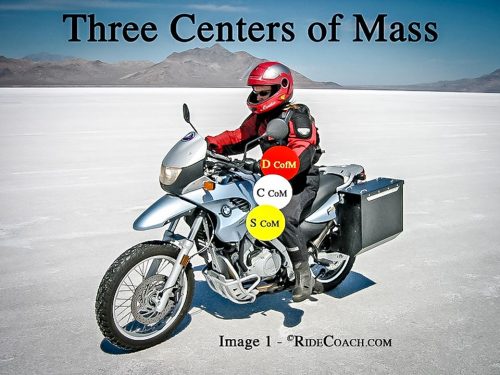

A motorcycle and rider have three centers of mass (aka, centers of gravity).

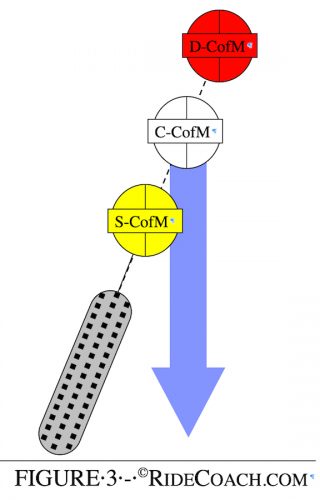

The motorcycle has a center of mass that does not move much relative to the frame. So I call it the static center of mass (S-CofM). The rider has a center of mass too, but because she can move around, I call her center the dynamic center of mass (D-CofM). Somewhere on a straight line between the static and dynamic centers is the balance point of the motorcycle, the combined center of mass (C-CofM). Stick with me on this physic stuff and it will really pay-off in a minute. Figure 3 shows a rider leaning in to a slow turn with her bike. This creates a tip-over problem because the down-force of gravity (the blue arrow) works through the C-CofM. Notice how far away from the tires the blue line hits the ground. The bike is out of balance.

This rider is out of balance. Her bike is tipped-in and she is too. Her helmet, spine, and butt are almost in a straight line over the seat. Her arms have about the same bend left and right which tells us she is not pushing her bike down and away. Except for looking down, her body mechanics would be pretty good if she was doing a faster turn.

SIDEBAR: When we talk about turns, it is sometimes confusing to say left or right and clockwise or counterclockwise. Instead, use the terms inside and outside. Inside means towards the center of the turn. The outside of a turn is the side away from the center.

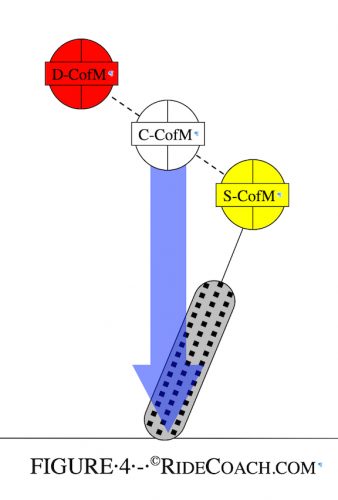

The rider in Figure 4 has moved her butt to the outside of the seat or, if she were standing, moved her weight to the outside footpeg. Her move to the outside also moved the balance point of her bike (the C-CofM). Now, the fall-line of gravity (blue arrow) is directly over her tires. She is balanced.

How far should you move your butt to the outside in a slow speed turn? It depends on how sharp the turn is. The tighter the turn, the more you need to move to the outside. In the extreme, your inside boot may come up off of the foot-peg. In training, we off-weight the inside footpeg in both seated and standing positions just to show what is possible.

Slow-speed turn arm position is also very important . If your outside elbow is not up and bent and your inside arm is not down and long, you are probably leaning-in rather than staying upright and gravity-neutral.

How To Do a Seated Slow Speed Turn

Slow turns are fun once you get the hang of them. To help you remember the different things to do in a slow turn, think of it as having three parts: Approach, Entry, and Exit.

Approach: Slow down before the turn. Check it out, make a plan.

Entry: Eyes UP, look where you are going.

Make steady power with your right hand on the throttle.

Control ground speed with your left hand on the clutch.

Use direct steering to start the turn.

Rise UP an inch or so and let the bike tip down under you.

Sit back down with your butt on the outside edge of the seat.

Exit: Eyes UP, look to your exit point.

Speed-up out of the turn with clutch or add some throttle.

Direct-steer out of the turn.

Rise UP an inch or so as the bike rotates UP under you.

When the bike is vertical, sit back down.

You will be back in the center of the seat.

Conclusion. Slow speed training is hard. Sometimes even harder than going fast. But once you really “get it” the pay-off is immense. No longer are you afraid to flip-a U-turn from a stop. No longer do parking lots or heavy traffic make you tense. Rough ground, rocks or water crossings become fun. Why? Because you just know you can do it. You did it in training, you did it in practice, now do it in the real world. That’s the emotional part. The can-do feeling, the sense of confidence and that wonder belief in yourself. It’s called pride and it’s okay to have it.

So what’s next? If there is interest we can do more on standing counter-balance turns. Also, did you happen to notice that I touched on something I call “Left Hand Speed Control?” That’s where you bring your engine RPM’s up to produce a kind of low-speed power called torque and to create a stabilizing force called gyroscopic precession (your bike doesn’t want to fall over!). And then you control ground speed with your left hand on the clutch. Cops do it. Trials riders do it. Racers do it and you can too. Be that will have to wait until next time.

About the Author: While it is clear that Ramey ‘Coach’ Stroud loves adventure, his passion is teaching. He has been recognized by the BMW Motorcycle Owner’s of America Foundation as their “Individual of the Year” for his training and safety programs. Coach has helped thousands of riders on four different continents. Although most of his time is spent helping professional racers bring home gold, he is also very, very good at helping new riders get started. Want to learn to ride a motorcycle well? Ramey ‘Coach’ Stroud is definitely your “go-to” guy! But there are only so many hours in the day, only so many riders he can see in person.

The next best thing is to read Coach’s articles or get his books. FREE ebook: